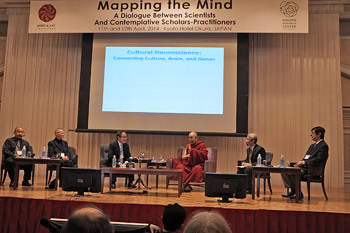

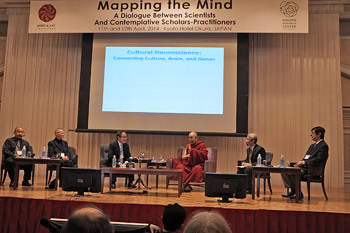

Kyoto, Japan, 12 April 2014 - The second day of the Mapping the Mind meeting began in a quiet business like way. Presentations began as soon as His Holiness had quietly taken his seat on the stage. Shinobu Kitayama, born in Japan, but now Professor of Psychology in Michigan, began, speaking about Cultural Neuroscience, with the observation that cultural context is important for understanding the human mind.

|

| Professor of Psycholog Shinobu Kitayama speaking

about Cultural Neuroscience during the second day of the Mapping the

Mind conference in Kyoto, Japan on April 12, 2014. Photo/Jeremy

Russell/OHHDL |

Clarifying what cultural neuroscience is he said that although humanity is one, it has multiple manifestations. This variability in cultural models combined with neuroplasticity means the brain may be moulded by cultural context. The brain is not a static entity, but can change as a function of experience. It may be shaped by ecological, environmental and cultural factors. As a biological organ the brain is also subject to genetic influences and there is evidence that these too may vary according to society and culture.

Kitayama suggested that the view of the self in the West, or at least Europe and North America is that it is independent. You choose your own friends and so forth; it has a disjoint agency. In other parts of the world, such as Asia, the self is more relational and interdependent; there is conjoint agency. He cited experimental findings that apparently show a difference in error related negativity response among those from the West with regard to self interest and the interests of others, which was not found among Asians.

His Holiness resisted this conclusion saying it was difficult to generalise because there are of course altruistic Americans and self-centred Asians. He suggested that findings involving Africans, and distinctions between people living in cities and in the country would be interesting. He also remarked that it would be interesting to see if male and female distinctions made any difference.

|

Zen Roshi Joan Halifax during her presentation at the second day of the Mapping the Mind conference in Kyoto, Japan on April 12, 2014. Photo/Office of Tibet, Japan

|

Joan Halifax, a Zen Roshi, drew on 40 years of working with the dying to give her presentation about compassion training. She said that compassion is generally considered to be the capacity to attend to the experiences of others, feeling concern for them, having a sense of what will serve them. It can also be described as caring for those who are suffering with a motivation to relieve that suffering. She explored a systems based map of compassion amenable to training developed to train care givers and medical professionals. She proposed that compassion cannot be taught; it is an emergent process. The training also takes account of reports that care givers and clinicians are subject to exhaustion and burnout and are often in need of care themselves.

The third presenter of the morning, Shinsuke Shimojo, who has received a number of Japanese awards and is currently an Experimental Psychology Professor at the California Institute of Technology, returned repeatedly to an illustration of the mind as an iceberg. His point was to show that the explicit conscious mind is only the tip of the iceberg. The significantly more extensive implicit mind is below the surface. He said certain aspects of the human mind traditional psychology and neuroscience have difficulty addressing. He suggested that an individual’s personality and emotional decision-making should be understood in a dynamic social context, paying attention to dynamic interactions between the brain and the social world. These are areas in which implicit mental processes play a key role.

|

His Holiness the Dalai Lama commenting during Experimental Psychology Professor at the California Institute of Technology Shinsuke Shimojo's presentation during the second day of the Mapping the Mind conference in Kyoto, Japan on April 12, 2014. Photo/Office of Tibet, Japan

|

Describing how a flea can be induced to give up jumping by confinement under a glass dish, Shimojo spoke of evidence of learned helplessness that characterizes a strain of depression afflicting Japanese. It’s a depression that has been calculated to cost the economy $25 billion. He suggested that the difference between being healthy and sick in this context involves not just the mental state, but also dynamic loops that include the body and social environment. He referred to implicit synchronisation among people, observable when people walk together. He stated that the March 11 Fukushima nuclear disaster is one of various crises that necessitate a more profound understanding of implicit aspects of the mind.

His Holiness declared he had a question to ask. He described friends who have developed a degree of concentration such that they can remain focussed on the object for 3-4 hours. Is this possible? Taking up the issue of different environmental factors he suggested that such a meditator ought to be able to continue his practice even in a big city. Through training you should be able to remain tranquil 24 hours a day.

“While I don’t have deep experience, I think I can see some improvement over the last 25 years. I’d be interested to know the effect of the completely dark days in winter in some parts of Northern Europe and the midnight sun in the summer. I sometimes call myself the sleeping Dalai Lama because of my fondness for having a good night’s sleep.”

His Holiness also pointed out that compassion needs to be combined with wisdom. Compassion without wisdom is weak.

“We are social animals,” he said, “and we can no longer remain in isolation. We are part of a greater whole. This is true of both Japanese and Tibetans. When people come to tell me about their difficult problems I sometimes tell them about mine in order to give them a broader perspective and the sense that they are not alone.”

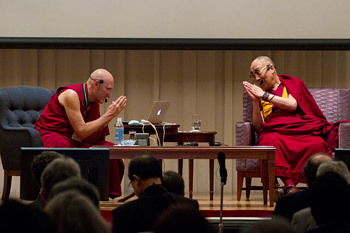

|

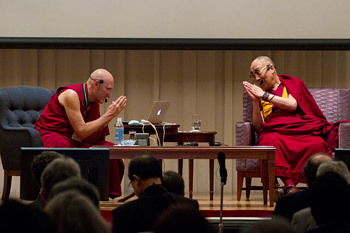

His Holiness the Dalai Lama thanking Ven Dr Barry Kerzin for his presentation during the second day of the Mapping the Mind conference in Kyoto, Japan on April 12, 2014.

Photo/Office of Tibet, Japan

|

After a break for lunch, Dr Barry Kerzin offered a mala or rosary as an analogy of the mind or consciousness, citing the string as indicating its continuity and the beads as like the moments of mind that follow one after the other. Its circularity is also indicative of the mind’s having neither beginning, nor end. He went on to describe the classic Buddhist presentation of 6 primary minds and 51 mental factors. Of the primary minds, 5 are concerned with the senses, the sixth being mental consciousness. This can be coarse, subtle and most subtle. The coarse mind is our ordinary mind; the subtle mind is, for example, the mind present during dream time when the senses are inactive. A more subtle mind occurs in deep sleep. Through training these implicit minds can be made explicit. The most subtle, non-conceptual, non-dual mind occurs at the time of death.

Dr Kerzin not only described the 8 visions that take place during the dissolution that takes place at that time, but also provided illustrations. These visions are reported to be like a mirage, billowing smoke, sparks like fireflies, a lamp in a darkened room, the light of the moon, red increase like a sunset, black near attainment and finally clear light. He mentioned that accomplished meditators can enter into and remain in that clear light for some time after clinical death has occurred.

“This non-duality you spoke of,” His Holiness said, “should be understood as a lack of distinction between subject and object.”

|

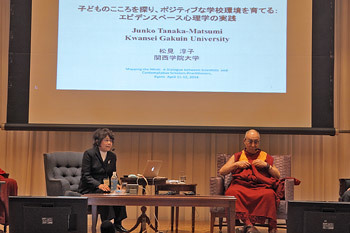

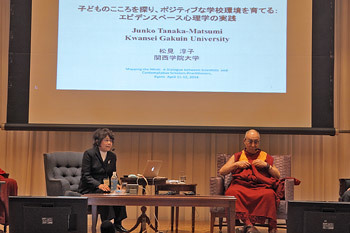

Dean of Humanities at Kwansei Gakuin University Junko Tanaka-Matsumi during her presentation on the second day of the Mapping the Mind conference in Kyoto, Japan on April 12, 2014. Photo/Jeremy Russell/OHHDL

|

After 20 years teaching clinical psychology in New York, Junko Tanaka-Matsumi is now Dean of Humanities at Kwansei Gakuin University. She gave a presentation about Mapping the Minds of Children, beginning by saying that children’s minds change from moment to moment. She pointed out that when you see that Japan comes second in the world for provision of science education it would appear that all is well with the Japanese education system. However, in the classroom there are children who cannot follow what the teacher is saying. They display disruptive behaviour such as not remaining in their seats. But because of the sense of homogeneity no special help or provision is made for them, and indeed their parents do not seek it, because they do not want their children to be singled out. She advised that simple steps like making clear to such children what they were meant to be doing and giving them a card to remind them can be effective. Reinforcement of positive behaviour in children also increases their self-esteem and encourages positive peer interaction.

His Holiness wanted to know the age of the children referred to; they were 7-9 years old.

The final presentation was made by Makoto Nagao who, graduating initially from Kyoto University, went on to lead a distinguished career in natural language processing and machine translation, among other things. He stated that the function of the mind is best mapped or revealed in conversation and applied this to the special area of developing care-giving robots. Such robots should be able to converse with those for whom they are caring. Importantly they need to be able to deal with inference from people’s demands in order to generate appropriate responses and proper answers. Dr Nagao suggested that developing robot dialogue systems will not only help those for whom the robots care, but could lead to clarification of how the mind reacts to external stimuli, so furthering understanding of mental function. This will be an unusual route to mapping the mind.

|

Makoto Nagao during his presentation on the second day of the Mapping the Mind conference in Kyoto, Japan on April 12, 2014. Photo/Office of Tibet, Japan

|

Dr Nagao confirmed that robots can be designed according to the purpose for which they will be used, whether it is care-giving, fire-fighting or dealing with damaged nuclear installations. His Holiness laughing said that of course a robot will not be able to display affection, but at least it will not get angry.

In response to a question about who he has in mind as benefiting from meetings like this he said:

“I always think of the 7 billion human beings alive today as physically, emotionally and mentally the same. Externally things may have been different, but even several thousand years ago our emotions would have been the same. The Buddha was once like us, but through persistence and hard work he transformed his mind. In this 30 year partnership with scientists we have learned many useful things and, unless they are merely being polite, scientists are learning a good deal about the mind too. Between us we are working on a curriculum to introduce secular ethics into the education system. Scientists are participating in this project not out of a wish for material reward, but because of the long term benefit it will provide. Our aim is a happier humanity and it won’t be achieved just through prayer or wishful thinking but by learning to deal with our destructive emotions.”

An appeal was made to everyone present to contribute to solutions to the problems that have arisen from the Fukushima nuclear accident. His Holiness mentioned that he was recently in nearby Sendai. He had no immediate answer to the situation because, as he said, the whole nuclear issue and generation of energy is complicated. He looks to a future when it may be possible to rely on solar power.

|

His Holiness the Dalai Lama and fellow participants and organizers of the two day conference on Mapping the Mind in Kyoto, Japan on April 11, 2014. Photo/Office of Tibet, Japan

|

Arthur Zajonc, President of the Mind & Life Institute in his closing remarks, came back to the idea of care. He drew attention to the developing educational curriculum ‘Call to Care’ and the three stages of care - receiving care, care for ourselves and extending care to others. In addition to thanking His Holiness for his presence, he thanked all the presenters and those through whose care and organization the meeting had successfully taken place. Adrian Freedman played a short traditional piece on the shakuhachi, the traditional Japanese bamboo flute, and brought proceedings to a fitting end.

Tomorrow, His Holiness goes to Koya-san, the location of the headquarters of the Shingon tradition of Japanese Buddhism.